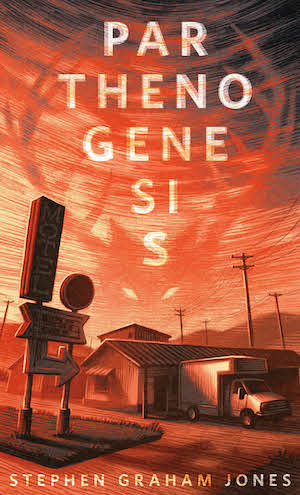

When their rental truck breaks down, two friends moving cross-country kill time by telling stories about the strange carving in front of the motel where they’re awaiting a mechanic . . .

“It’s a bear, isn’t it?” Matty asks, his voice riding a ramp up. “That’s what they look like?”

He’s talking about the ten-foot-tall wooden statue in front of the one-story motel in a town in western Colorado neither he nor Jac had planned on stopping in for a whole afternoon. The moving truck they rented had other ideas. For two hours now, after way too much coffee in the diner across the street, they’ve been sitting in the grassy shade of the motel, moving only when the sun melts a few degrees over, onto a hand, an elbow, the shoulders.

“But bears don’t sit on their haunches and . . . howl like a wolf, do they?” Jac asks back, galloping her fingers on the ground in thought.

Matty nods, considering this.

The bear’s definitely in a wolf pose, its snout lifted to an imaginary moon.

“Awoo-oo,” Jac adds, her head tilted back as well.

The company they rented the truck from to move across the country is certain the mechanic they’ve contracted will be there in thirty minutes. And then thirty more minutes.

Matty squints up at the statue as if checking for its wolfness, its bearness.

“I mean, okay, if we’re being technical,” he finally says, shrugging as if reluctant to forge on, “then I guess wolf-bears also don’t really have actual elk antlers on their heads either, do they?”

“Oh, so you want it to make sense,” Jac says, and punctuates this by pulling his blue Icee over. She shakes it to get the drinkable stuff under the straw and slurps deep, flirting with brain-freeze. She doesn’t clean the straw, either. Not because they’re together—they’re not, they promised not to ever mess things up that way—but because they’ve known each other since freshman year of high school, when Jac was selling handstamps for a club in the city, five dollars a pop, refundable if the stamp doesn’t get you in the door.

The reason they’re driving a moving truck across the country together is that neither has enough to fill a truck, so it made sense to share. Jac was the one with the idea to move, just for a reset now that high school was ten years ago somehow, but Matty wasn’t hard to talk into it.

Matty would rent a chair in whatever salon would have him, Jac would paralegal here and there, they’d each pay their separate rents, go on their dates with other people, and life would keep happening. Just, in a new place, now. With a different backdrop. But then, at the gas station a quarter-mile back, the moving truck had refused to start, even though they’d given it a tankful of premium.

“If you want it to make sense,” Jac goes on, leaning back to really luxuriate in this, “then . . . here’s what happened.”

The way she hits that last part hard, and the space she leaves after that, is part of their game. It’s an invitation into make-believe, to be anywhere but where they are. But she’s not sure Matty remembers, after all these years.

“Is this back when people were stupid?” he dredges up, pitch-perfect.

Jac smiles up into the sky, eyes closed, and nods.

“It’s back when magic was real, yeah,” she says.

“Same thing,” Matty says, lying onto the grass all at once and not undramatically.

All they need are a couple of illicit cigarettes and they could be fourteen again.

“When Sandra Gleason bought the motel out of receivership,” Jac leads off, talking slow at first to make it up just right, “she decided that the way to draw people in off the interstate was with local flavor. With art.”

“Sculpture,” Matty says, playing along. “Someone from the last regime—”

“‘Regime?’” Jac asks, sneaking a look over to him.

“The previous owners who ran it into the ground,” Matty says, his tone lower because this is so obvious it’s practically beneath saying.

“Go on,” Jac says all the same, hungry for the salacious details.

“The previous motel dictators had a suggestion box, but they never checked it. Then Sandy—”

“Sandra. She hates when people call her Sandy.”

“Ms. Gleason, renovating, popped the back off that suggestion box and read how one couple from Ohio stood in line at the registration desk waiting their turn for ten minutes, and nearly left, disgusted.”

“People from Ohio are historically impatient.”

“But Ms. Gleason thought—”

“She thought that sweet retired couple from Ohio wouldn’t have been so frustrated if there had been some invigorating art right outside the window that they could have studied while standing in line.”

“Was it her brother who was a chainsaw artist?” Matty asks, leadingly, always trying to inject a piece into their stories that might stump Jac.

“It was, it was,” she says, right in stride. “But ever since the inheritance squabble about which no Gleason will ever speak again, well . . .”

“Say no more.”

“So she solicited bids and pitches from local artists, like you do.”

“Bringing in an out-of-towner would be bad for business.”

“The first artist who answered the call was a retired welder who turned tractor parts into old-fashioned robots.”

“‘Old-fashioned?’” Matty asks, reaching over for his Icee. Jac nudges it into his fingers for him.

“Retro, like. What we imagined the future would be, back in 1950.”

“Back when we were stupid, yes, yes,” Matty says.

“But, while his bid was low enough, he couldn’t have a robot for the motel until the following summer, and Sandra was looking to open the doors for business again in two months, for ski season.”

“So she widened the net, so to speak.”

“The next bid was from a stoneworker—actually a reformed cheerleader who had started out carving Easter Island heads from foam blocks, for parade floats. But—”

“She got hooked, imagining the bodies that would someday stand up from under those heads, dirt and roots falling away.”

“The problem with her work, though, was that granite invites spray paint, and Sandra didn’t want to have to commit time every week to cleaning obscenities from her statue.”

“Who would?”

“She tells the third artist that something in keeping with the local fauna would be nice, wouldn’t it?”

“And this isn’t Sumatra, so no tigers. It’s not Africa, meaning elephants were out. And it’s not South America—no peccaries.”

“You mean capybara?”

“Are they not the same thing?”

“And,” Jac says, “what’s local to this altitude?”

“Bears,” Matty says. “Bears and wolves. And that king of the jungle, the mighty elk.”

“King of the forest,” Jac corrects, gently. “They agree on a price, a deadline, but . . .”

Now her voice is riding that ramp up, leaving blank spaces for Matty to fill.

“The beetles came,” Matty pulls right out of the ether, his voice dripping with sadness. “They were, um—they were Dutch elm hickory beetles. The ones that bore those crawly little open-top tunnels in trees, like tracing their circulatory system, or carving one out.”

“Dutch elm hickory . . .” Jac repeats, pressing her lips together to keep from smiling.

“Otherwise known as the fire beetle,” Matty says, sitting up all at once, his hands up before him, fingers spread with the danger these beetles portend.

“So . . . the forest burned down?” Jac asks.

“From the inside,” Matty whispers. “Fire beetles bore into the trunks of every tree they can, and the friction of their little legs moving forward generates enough heat that—that they start to glow with heat, like burners on a stove. It’s why they evolved that special ceramic belly armor.”

“To keep their carapaces and thoraxes from burning.”

“Is that really how you plural that?”

“It is now,” Jac says, looking up the tall, tall statue. “What this beetle infestation meant to the third artist was that her precious wood supply was greatly reduced.”

“It nearly tanked the stock market.”

“So she only had one tree trunk with which to satisfy this order . . .”

“But fulfill that order she did. A bear, a wolf, an elk.”

Jac swipes the Icee away, shakes and slurps, then, bowing forward on her knees like a proper supplicant, careful to keep her face down, she ceremonially places the cup at the foot of the statue, splashing the last drink up on its inner calf.

“Oh, great bearwolfelk,” she says. “Please accept this offering, and know that, in your presence, we weren’t the least bit bored or fidgety.”

“And we’re from Virginia,” Matty says, on his knees beside her now, ceremonially holding his hands up in approximation of antlers, and raising his own mouth to simulate a long, mournful howl.

Jac hip-checks him, he falls over laughing, and a mother pushing her stroller past hurries her step, which only makes Jac and Matty laugh more. They walk down to the gas station restroom one more time, meet at the ice fountain for the free refill the sign guarantees, and by dusk the mechanic’s showed up, done his grumbly thing, and then they’re making time again. Heading west, leaned over their headlights.

At least until the state line, when the moving truck’s gauges ring the alarms.

“No, no, c’mon,” Jac says, patting the dash like this is a good truck, a good truck.

But it’s not.

“This isn’t happening,” Matty says, shaking his phone like that can make it get a signal.

But it is happening.

The truck dies, the power steering and power brakes evaporate, and—it’s not an emergency, it’s just where they are—Jac directs the truck onto the shoulder, and up the first few yards of a runaway-truck ramp. The sand glitters in the headlights. Jac turns them off.

“What was that about ‘back when people were stupid?’” Matty says.

“Meaning?”

“My idea to move across the country.”

“And I’m the one who found this discount truck.”

“But I’m—”

A long, lonely howl interrupts, wending its way in from the great darkness out there.

Jac and Matty make concerned, about-to-laugh eyes to each other, roll their windows up.

“What now?” they ask at the same time.

“Walk?” Matty tries, not hopefully.

“Says the man who doesn’t have to think about the dangers of that at night,” Jac says.

“You think they’re going to like my blue hair?” Matty asks.

“They?”

“Whoever lives out this far.”

“This doesn’t feel like an adventure anymore,” Jac says, hugging the wheel to study the darkness before them.

“We could sleep in back with the furniture,” Matty says with a noncommittal shrug, peering over to gauge whether this will fly or not.

“And suffocate in the night,” Jac tags on.

“Leave the door cracked.”

“So a hook-handed maniac can paint the walls with our insides.”

“Subject change, please.”

“Maybe Sandy Gleason will come save us,” Jac says.

“You mean ‘Sandra?’” Matty asks.

“I’m saying it like that to get her goat,” Jac says, slumping back into her seat in defeat. “She’ll want to come give us what for. And maybe we hitch a ride after she chews us out.”

“We can get a room at her motel.”

“Where you check in, but you never—”

“Don’t say it!”

“I’m sure it’s a very nice motel,” Jac says, then spooks her voice down a gear. “But the boiler, it doesn’t run on wood, it runs on—”

“Stop! Stop stop stop!”

Jac’s shoulders hitch with laughter. She hits the top of Matty’s thigh with the side of her fist.

“You’re so easy,” she tells him.

“And you’re so mean,” he tells her back, albeit lovingly. “At least there’s all these stars, right?”

Jac leans forward, squints into the darkness at all the flecks of light.

“But it was cloudy, wasn’t it?” she says. “It even sprinkled on us back there, didn’t it?”

It did. It’s how they found out the wipers on the truck were worse than not having wipers at all.

“Clouds blow away,” Matty says, talking himself into it. He flourishes his arm over the dash, presenting all the stars out there for proof.

“But stars are white . . .” Jac says, popping her door open.

The dome light comes on and she nuzzles her toe into the hinge, finds the button, lets the darkness shroud over them again.

She’s right about these thousand points of light: they’re . . . flickering orange?

“Close it, close it, please,” Matty says.

She looks over to be sure he’s serious, then—slowly—she does. The deep clap of the door resounds.

“Fire beetles . . .” she says.

Matty’s back is straight against the seat, his feet are pressed hard to the floor, his hands are balled into fists, and his eyes are closed against this.

In sympathy, Jac clicks the locks.

Two hours later, her phone dead, Matty’s barely holding on, they make a pee pact. It means they’ll go out together to do it, but while each one’s peeing, the other will keep his or her hand on the pee-er’s shoulder.

Their shoes crunching through the sand is deafening, but the blanket of pine needles farther out in the darkness, wet from the rain, are worse—not loud, but the kind of squishy it’s hard to trust.

“Sing, sing, something loud,” Jac says, squatting, Matty’s hand clamped tight to her shoulder.

Matty sings the fight song from their high school. It’s the only thing he can think of.

For his turn, Jac sings it just the same, to drown out first the long sound of nothing, then the sound of trickling, then splashing.

Then nothing—Matty’s pinched it off.

“What?” Jac says. “Another song?”

“Did you hear that? A . . . I don’t know. A huffing.”

“Huffing?”

“What huffs?”

“Your imagination,” Jac says, and starts to turn to him, realizes his fly’s still open.

“Sing, sing!” Matty commands.

She does, he finishes, but then, because there are no sinks, less soap, they discover they don’t really want to hold hands for the walk back to the dark monolith the truck’s become, against the flickering orange stars crawling through the trees.

Back in the cab of the truck, which is a slow process at first, then a desperate rush, like diving into bed fast enough to beat the light you just turned out, Jac says, “Whoah.”

“Whoa what?” Matty says.

Jac directs his eyes down to where she can’t stop looking: the console between the seats.

A full blue Icee is there.

Matty flinches away, presses himself against his door so hard that Jac locks it from her side, so he won’t spill out.

“This is wrong, this is bad,” Matty’s saying.

“Somebody else was in here,” Jac says, in wonder. Then, dragging a finger line in the condensation beading on the clear cup, she adds, “That sign did say free refills, though, didn’t it? Maybe they take customers very seriously out here, where there’s hardly any customers. You have to really impress the few there are.”

“I can’t do this anymore,” Matty says.

“The couch?” Jac asks. When Matty’s finally able to pull his eyes from the Icee, she tilts her head to the back of the truck.

Matty nods.

“Wait, wait,” he says though, when they both open their doors. “We can’t—if we both get down to go back there, then we’re alone on either side of the truck, aren’t we?”

Jac nods, following his logic.

“And how do you know I’m me when we meet?” he says.

“Because you will be.”

“Will you?”

Jac peers into the darkness on her side of the truck. The stars out there are scrawling lava trails into the trees.

“Okay, yes,” she says, and, careful not to dislodge the volcano lid of the Icee in the cupholder, she spiders her way over to Matty’s side of the truck. She’s practically sitting in his lap.

“On three,” Matty says, and pops his door handle.

When the door doesn’t open, he scrabbles desperately at it, a forlorn noise in his throat, burbling past his lips.

“Here, wait,” Jac says, and reaches across the console for the ignition key, still in its place on the steering column. She presses the fob and the door locks clunk open along with the door, spilling them out in a pile.

They come up spitting sand, looking every direction at once.

“When people were stupid . . .” Jac says again, their chorus for the night, now.

“And not liking this even a little,” Matty adds.

Jac stands, moving to heave the door shut, except suddenly Matty’s hand is there, stopping her.

“Too loud,” he says. “There might be ears out there. Connected to eyes. And mouths.”

“Paranoid much?” Jac asks.

“It’s called survival instinct.”

Holding hands now, who cares about bathroom germs, they skirt the side of the truck, keeping their back to it, and then, remembering the padlock too late, they have to make their way back to the cab, for the key in the glove box.

“My heart can’t take this,” Matty says.

Jac squeezes his hand tighter, to keep him from exploding up out of his skin.

As quietly as they can, they twist the key in the padlock. Jac works the grimy strap at the bottom of the door out. The problem now is how to pull this loud, loud door up.

“They can’t be out there like that,” Matty says, about the stars. About the fire beetles.

“That Icee shouldn’t be cold like that,” Jac says.

“It shouldn’t be there at all,” Matty says, cranking his head around all at once, like to catch something trying to hide behind them.

“What?” Jac asks, looking as well.

“I’m going to open it now,” Matty says like talking himself into it, then pulls up on the strap all at once, yanking until the springs or counterweights or whatever take the door and rattle it up all at once in a rush like thunder made of great thin sheets of metal.

“Announce us, why don’t you,” Jac says.

“They’re not real,” Matty says. “Fire beetles.”

Inside the truck’s cargo box, it’s inky black. Velvet-black. No stars.

“Back when people were stupid . . .” Matty says again, squeezing Jac’s hand hard now.

“This is smart, this is safe,” Jac says, and palms her phone to light this interior space up. But of course her phone’s dead. And Matty’s is up in the cab.

“What’s that?” Matty says.

Their eyes are adjusting, slightly.

Inside, there’s something tall, regal, pointed, and . . . woody?

“Can’t be,” Jac says. But she’s not stepping forward.

Behind them on the interstate, a truck whines around the corner of this long downhill. When its lights line up with Jac and Matty, it makes their shadows plunge into the cargo box of the truck, which feels for a moment like a mistake, like their shadows are going to stick in there, and then snap Jac and Matty in with them.

But the headlights also reveal, for a split instant, Matty’s coatrack. The one his granddad made for his grandma, seventy years ago. His one family heirloom.

He finally breathes, shakes his head.

“I don’t think we’ll suffocate,” Jac says, and, using the handrail, steps up onto the wide rear bumper. She holds her hand back to pull Matty up.

He lets her, and they balance there for a moment, not outside, not quite inside.

“I’m not going to be able to sleep,” Matty says.

“Sleep is for beds,” Jac says. “Tonight’s about standing guard.”

Together, they step in, the truck’s springs creaking, adjusting to their slight weight. Then those springs adjust more. A lot more. Enough that Jac and Matty have to balance with their arms, their fingertips trying to find a wall.

As one, they look back to what could be so heavy.

Silhouetted in the wide doorway against a backdrop of a thousand tiny, crawling campfires, is a bear standing up on two legs, a bear with a long wolfy snout. A bear with a wide rack of elk antlers.

Instead of making sense—of being this or that or the other, not all three at once—it reaches up for the dirty strap at the bottom of the door and pulls it down hard in front of itself.

Matty and Jac fall back onto the couch. They’re clutching onto each other. They’re breathing too fast, too deep.

“That wasn’t—” Matty says.

“Couldn’t have been,” Jac assures him.

Which is when a hand from behind the couch claps down onto Matty’s left shoulder. Another settles onto Jac’s right shoulder.

They flinch and wriggle away. From the metal floor in front of the couch, they look up.

It’s a woman. She’s wearing a flannel shirt, jeans, and has her hair up under a scarf, reading glasses hanging around her neck. She’s staring down at Jac and Matty, her eyes intense, like she’s trying to catalog them, make sense of them.

“Sandy Gleason?” Jac has no choice but to say.

“Sandra,” Sandra Gleason corrects, her delivery getting across how tired she is of having to make this distinction.

“No, no, we were only—” Matty says.

“You’re not real,” Jac says. Insists.

“Real, not real,” Sandra Gleason says, stepping neatly over the couch and plopping down, then cocking an appreciative eye at the door when the padlock out there clicks shut. “Is that really a big concern out here in the darkness, you think?”

Jac blurts out, “We’re sorry, we didn’t mean—”

“We were just having fun!” Matty finishes.

“Me too,” Sandra Gleason says, and angles over to reach behind the couch for something, still speaking: “I should tell you, though. My brother and I, we finally reconciled—did you not get to that part? Oh, yes, yes. He even lets me use this, now.”

What she hauls up, sets on her lap like the trusty thing it is, is a toothy chainsaw.

Matty and Jac kick hard away from this, into the door, one of them yipping, one groaning, both of their dreams of a new backdrop for their lives screaming away when that chainsaw rips to life, not stopping to sputter, just instantly revving higher and higher.

Up in the cab, from the shaking of the truck, a clump of the drops perched on the clear side of the Icee pool together, are now heavy enough to zigzag down the side of the cup, eating up more and more condensation on the way, until it’s less tears crying, more just wetness tinged berry blue.

Outside the truck, the stars in the trees scribing orange lines in the night, spelling out words no one will read, the silhouette of a bear that’s a wolf with elk antlers looks up from the tuft of grass it’s tugging on with its mouth, and when the round tip of that furious chainsaw chews through the side of the cargo box for about six inches, this bear cocks its elk ears, twitches its wolf nose, its great antlers cocked at an inquisitive angle, but when the blade sucks back in, this creature with the heart of a fairy tale goes back to pulling at the stubborn grass.

It’s not easy with sharp teeth, but it’s got all night, doesn’t it?

Unlike—the little two-stroke engine in there chugging down now, from the deep work the blade’s doing—unlike Jac and Matty, who, if they’re lucky, will find themselves carved into a piece of art to keep those pesky Ohioans out of the suggestion box.

“Parthenogenesis” copyright © 2024 by Stephen Graham Jones

Art copyright © 2024 by Brian Britigan

Buy the Book

Parthenogenesis

That did not end as I expected. It did leave me needing to sleep with the lights on… and with a smile on my face.

How did I miss this one? Thank you, Stephen, for this funny and gruesome tale. Always looking forward to more stuff from you, you’re the main engine of my efforts to still try to do this writing thing that keeps slipping from me.